КЛАСС НА ОТКРЫТОМ ВОЗДУХЕ: РЕШЕНИЕ ПРОБЛЕМЫ «ДЕФИЦИТА ОБЩЕНИЯ С ПРИРОДОЙ» У ДЕТЕЙ

КЛАСС НА ОТКРЫТОМ ВОЗДУХЕ: РЕШЕНИЕ ПРОБЛЕМЫ «ДЕФИЦИТА ОБЩЕНИЯ С ПРИРОДОЙ» У ДЕТЕЙ

Аннотация

В статье исследуется влияние мировой урбанизации и цифровизации на детей, с особым вниманием к явлениям, известным как «дефицита общения с природой» и «расстройство недостатка природы». Ограниченный доступ к окружающей среде, чрезмерное использование цифровых устройств и закрытая школьная среда способствуют возникновению ряда психологических и физических проблем у молодых людей, включая повышенный уровень стресса и тревоги, социальную изоляцию, снижение физической активности, дефицит витамина D и затруднение здорового развития.

В исследовании анализируется роль школьной среды как ключевого пространства, где дети проводят значительную часть своего времени. В нем обосновывается необходимость интеграции природы в образовательный процесс и предлагаются основные рекомендации по преобразованию существующих школьных зданий. Эти рекомендации направлены на улучшение доступа дневного света, визуальной открытости и пространственной связи с внутренними дворами и зелеными зонами.

Особое внимание уделяется концепции открытых классных комнат, рассматриваются их виды (стационарные, мобильные, интерактивные зеленые пространства и «зеленые школы»), проблемы их внедрения, а также международные примеры из Финляндии, Австралии и других стран.

В заключение в статье предлагается разработать многофункциональную передвижную мебель для открытых классов, которая послужит практическим инструментом для адаптации существующей школьной инфраструктуры к потребностям современного образования и восстановления связи между ребенком и природой. Представлена модель мебели, включающая в себя место для сидения и поверхность для письма. Кроме того, обсуждаются различные варианты расположения мебели в открытых классах с целью достижения оптимального визуального контакта между учащимися и учителем.

1. Introduction

Global urbanization represents one of the key challenges of the modern world. New technologies have become dominant in contemporary life and in the urban environment. Today, life seems unimaginable without mobile phones, tablets, laptops, or computers. Robots and artificial intelligence are increasingly entering our lives, to a great extent replacing humans in various sectors of production and services.

The world is changing — people’s lives are changing—and these transformations have led to significant problems, particularly among young generations . Digitalization has fostered a more isolated and introverted lifestyle. The expression "my home is my castle" has acquired a new and highly relevant meaning. We have become prisoners within our own homes, connected to the surrounding world solely through technology and digital devices. Without realizing it, we are distancing ourselves from nature, which results in a range of adverse consequences.

Both adults and, most importantly, children are exposed to these modern challenges. For children growing up in the digital era, access to nature is not merely a matter of leisure or recreation — it is an essential component of their healthy development. Unfortunately, an increasing number of children suffer from what has become known as "nature-deficit disorder", a term used to describe the lack of physical, emotional, and cognitive benefits that nature provides .

The biophilia hypothesis suggests that humans possess an innate tendency to seek connections with nature and other forms of life, making environmental interaction a fundamental human need . When this connection is disrupted, especially during childhood, negative developmental consequences may arise.

This paper explores the role of the school environment in addressing nature deprivation, with particular emphasis on outdoor classrooms as a potential architectural and pedagogical solution.

2. "Nature-Deficit Syndrome" and "Nature-Deficit Disorder"

Nature-deficit syndrome is a relatively new term referring to a condition in which individuals — particularly children — experience limited contact with the natural environment, resulting in adverse effects on their psychological and physical well-being . The term is broad in scope and is frequently used both in scientific literature and in popular discourse. It serves as a general, descriptive concept that encapsulates the underlying causes and consequences of reduced interaction with nature.

The term "nature-deficit syndrome" was introduced in 2005 by the British primatologist and environmentalist Valerie Jane Morris Goodall. She used it to describe the phenomenon whereby people — especially children — are increasingly disconnected from the natural world, leading to detrimental effects on their mental and physical health.

In contrast, "nature-deficit disorder" represents a more recent and specific concept, often used in the context of psychological and behavioral issues associated with the absence or severe restriction of interaction with natural environments. This term emphasizes the pathological or dysfunctional aspects of the condition and may be interpreted as a form of disorder in human functioning caused by the lack of connection to nature. It encompasses the psychological and behavioral symptoms that emerge as a consequence of the disrupted human–nature relationship.

The concept of nature-deficit disorder was popularized by American author and environmental advocate Richard Louv in his influential book Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder (2005). In this work, Louv describes the psychological, emotional, and physical problems that manifest in children as a result of insufficient exposure to nature. His primary goal was to draw public attention to the declining amount of time children spend outdoors and in natural settings, as well as to the negative consequences of this trend. Since its introduction, the term nature-deficit disorder has been widely adopted across educational, psychological, and environmental fields.

2.1. Causes and Contributing Factors

The causes and contributing factors underlying both nature-deficit syndrome and nature-deficit disorder are largely identical. In practice, the term nature-deficit syndrome is more frequently encountered, more widely recognized, and generally accepted as an umbrella concept encompassing the broader spectrum of contemporary issues related to human disconnection from the natural environment.

The primary causes leading to the emergence and growing prevalence of nature-deficit syndrome (though these factors substantially overlap with those associated with nature-deficit disorder) include the following .

· Excessive urbanization and limited access to green spaces. The destruction of significant green areas, deforestation, and the removal of trees contribute to reduced exposure to natural environments. In recent years, large-scale forest fires have also emerged as a major factor in the ongoing degradation of nature.

· Excessive use of technology and digital devices. The rapid development of technology has created a highly digitalized daily routine, leading to reduced outdoor activity and interaction with the natural world .

· Concerns regarding children’s safety outdoors. Heightened fears about urban insecurity and perceived dangers in public spaces discourage outdoor play and exploration.

· Lack of structured educational programs promoting interaction with nature. Many schools lack curricula designed to facilitate outdoor learning, and traditional school buildings often remain closed, inward-oriented spaces—a legacy of outdated educational models.

· Social and economic barriers. Increasing digitalization and social isolation contribute to psychological and economic constraints that limit opportunities for meaningful engagement with the natural environment.

2.2. Symptoms and Manifestations in Children

The symptoms and manifestations of nature-deficit syndrome are relatively easy to identify. Although the phenomenon primarily affects children, it can also be observed among adults .

Children affected by nature deprivation frequently exhibit the following characteristics:

· Obsession with screens and video games, including a pathological attachment to digital devices and virtual entertainment.

· Insecurity or discomfort during outdoor activities, and a strong reluctance to participate in organized outdoor play.

· Increased susceptibility to stress, anxiety, and depression.

· Reduced physical fitness and overall health.

· Lack of interest in nature and environmental issues.

· Apathy toward real-world events and surroundings.

· Impaired social interaction and communication skills .

· Tendency toward introversion and withdrawal.

· Frequent outbursts of anger or aggression.

· Blurred perception of moral boundaries between right and wrong.

2.3. Impact on Mental and Physical Health

The lack of contact with nature has a significant impact on both the mental and physical health of children. This deficit in the human–nature connection contributes to heightened levels of stress, anxiety, and depression, while simultaneously weakening the immune system and reducing overall physical fitness.

In environments with limited exposure to natural elements, children frequently experience difficulties with concentration, social development, and emotional stability. The growing inability to maintain attention during classroom activities is also closely linked to this emerging syndrome, which is itself a consequence of diminished contact with nature, resulting in excessive alienation and social withdrawal.

Consequently, the absence of regular outdoor activity fosters sedentary habits, increasing the risk of obesity, vitamin D deficiency, and chronic cardiovascular conditions. The overall shortage of natural stimuli leads to a general decline in quality of life and a distortion of healthy developmental processes .

3. Vitamin D Deficiency in Children

One of the most essential vitamins for the proper functioning of the human body is vitamin D, which plays a particularly crucial role in the healthy development of children. It supports bone and dental health as well as immune system function. Vitamin D is fundamental for the absorption of calcium and phosphate from food, processes that are essential for the formation and maintenance of strong bone structures .

A deficiency of vitamin D in children can lead to serious health problems, including rickets — a disease that causes bone deformities, resulting in soft and fragile skeletal structures. In addition to skeletal issues, vitamin D deficiency often leads to a weakened immune response, reduced muscle strength, and an increased risk of chronic illnesses.

The primary cause of vitamin D deficiency is insufficient exposure to sunlight, as the human body synthesizes the vitamin through the skin under the influence of ultraviolet (UV) rays. In modern contexts — where children spend less time outdoors and frequently use sunscreen— vitamin D levels tend to be suboptimal. To maintain adequate health, dietary supplementation through foods rich in vitamin D or the use of vitamin D supplements is often necessary.

4. Strategies for Reducing the Effects of Nature Deficit

The current situation is a natural consequence of the technological boom of recent decades. It is unrealistic to oppose technological progress or its integration into everyday life, as digital innovations have become deeply embedded in modern society. Nevertheless, while technology has transformed established notions of a healthy lifestyle, it remains possible — and indeed essential — to improve the environments in which children spend most of their daily lives.

Children typically spend around eight hours per day at school, five days a week. Therefore, the school environment must be designed and organized in a way that promotes children’s psychological and physical well-being. Different countries are adopting various approaches to improve educational settings and to transform school buildings and curricula into healthier, more nature-inclusive environments.

Traditional schools are commonly characterized by enclosed classrooms and limited opportunities for outdoor physical activity. Although the effectiveness of conventional education is well documented, an increasing body of research highlights its potential negative consequences for children’s health and development, primarily due to insufficient exposure to nature. This is particularly relevant in Bulgaria, where approximately 90% of school buildings are inherited from a previous socio-political system that emphasized "closed education" — a model based on strict discipline, standardization, and isolation from the outside environment , .

By contrast, outdoor and "green school" environments are associated with increased physical activity, social interaction, and empathy toward nature. Learning in natural settings has been shown to enhance concentration, reduce stress, and support students’ emotional well-being. This represents a new approach to organizing the educational process — one that seeks to reintegrate nature into learning. However, achieving this goal requires not only state-level initiatives but also the active participation of school administrators, teachers, pedagogues, students, and parents.

There are several practical ways to implement such transformations:

· Maximizing natural light within classrooms throughout the day.

· Designing adjacent courtyard areas (particularly for ground-floor classrooms) with large glazed openings that visually and physically connect indoor and outdoor spaces.

· Enhancing transparency in common areas through skylights, roof windows, and floor-to-ceiling glazing ("French windows").

· Promoting visual openness in the educational process through glass walls facing corridors, foyers, and even façades.

· Developing outdoor classrooms to facilitate a greater number of lessons in open-air settings, which may include:

– Permanent, stationary structures located in natural surroundings;

– Mobile or modular units adaptable to various locations;

– Weather-resistant structures suitable for use in all seasons.

· Creating "nature laboratories" for observing plants, animals, and natural phenomena.

· Integrating the natural environment into the teaching of subjects such as biology, ecology, geography, and art.

· Establishing school gardens where students can cultivate and care for different plant species.

· Encouraging interactive outdoor activities, including:

– Educational excursions, nature walks, and observation programs;

– Games involving plant identification, ecological mapping, and creative work with natural materials.

· Introducing sustainable and eco-friendly materials, such as:

– Educational tools made from natural or recycled resources;

– The use of natural elements — stones, branches, wood, and leaves—in learning activities.

· Applying technologies that foster interaction with nature, including:

– Mobile applications and electronic tools for monitoring natural phenomena;

– Photo and video blogging for documenting outdoor observations.

· Engaging the community through:

– Educational programs linked to local environmental projects;

– Partnerships with ecological organizations and experts for practical workshops.

Architects play a critical role in shaping learning environments. They can provide guidance on how modern schools and their outdoor spaces should be designed to align with current educational and environmental needs. While designing entirely new schools allows for full integration of these principles, the greater challenge lies in adapting existing structures to contemporary requirements. The question, therefore, is how we can respond to the social and environmental challenges of modern society in order to foster a new, psychologically and physically resilient generation , .

One of the most effective solutions may be the creation of outdoor classrooms and the reorganization of the learning process so that children spend a greater portion of their school day outdoors. This raises several important questions:

· How can such outdoor classrooms be designed and implemented?

· What criteria and requirements should they meet?

· How do climatic conditions influence their use?

· What materials are most suitable for their construction?

These questions form the foundation for developing an architectural and pedagogical framework for reconnecting education with nature in the context of the 21st century.

5. Outdoor Classrooms

The concept of outdoor classrooms is not a new idea, nor is it an untested one internationally. In many countries, learning in outdoor settings has become a well-established and integral part of the educational system. However, for Bulgaria, this approach remains relatively novel — not due to a lack of awareness, but rather because only a small number of schools have implemented such spaces, particularly in large urban areas .

Introducing outdoor classrooms poses a number of challenges. It requires significant organizational adjustments, careful architectural planning, and thoughtful integration into the existing educational process. Designing and constructing outdoor learning spaces that can be used throughout the year — across different subjects, teaching methods, and class sizes — demands both infrastructural innovation and pedagogical flexibility.

Nevertheless, the development of outdoor classrooms represents a promising direction for enhancing educational environments, promoting children’s connection with nature, and improving their mental and physical well-being.

5.1. Challenges and Opportunities

Despite the strong potential of outdoor classrooms to enhance the learning environment, several challenges and limitations need to be addressed in order to ensure their effective implementation.

Key challenges include:

· Climatic conditions, which often impose restrictions on the use of outdoor spaces throughout the year;

· The need for investment, both for the creation and ongoing maintenance of such educational environments;

· Adaptation of teaching methods to the specific conditions, opportunities, and dynamics of outdoor learning;

· Identifying suitable locations and redesigning existing schoolyards or nearby natural areas to accommodate outdoor classrooms.

At the same time, these challenges present opportunities for innovation in school design and pedagogy. The integration of nature-based learning can inspire interdisciplinary collaboration between educators, architects, and local communities, leading to healthier, more engaging, and sustainable educational environments.

5.2. Models and Examples

Outdoor classrooms represent innovative educational spaces that transform part of the traditional learning process into an opportunity for experiential learning in direct contact with nature. Several approaches can be adopted in the realization of this concept:

· Permanent structures, as shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1 - Permanent amphitheatrical wooden/metal seating structure for outdoor learning

Note: source – Streetlife Outdoor Classroom Solutions

This model involves the construction of fixed wooden or metal facilities specifically designed for outdoor educational activities. It is suitable in cases where there is sufficient unused yard or open space that can be permanently designated for this purpose. However, within already existing school complexes, such an approach can be challenging to implement due to spatial and infrastructural limitations.

· Mobile classrooms:

These are movable learning spaces that can be relocated and used in various outdoor settings. This approach is more feasible for existing school environments. It relies on the design of lightweight, mobile, and multifunctional furniture and structures — such as modular desks and benches — that allow for flexible configurations and can be adapted to different outdoor areas within the school grounds.

· Interactive green zones, such as those depicted in Figures 2 and 3:

Figure 2 - Outdoor learning area at Colegio Maya School featuring natural and modular

Note: source – Learning Landscapes Design

Figure 3 - Outdoor classroom installation at Court of North Carolina Campus (2010)

Note: source – NCSU Digital Library Archive

These include gardens, ecological observation areas, and small experimental nature zones near schools. Such spaces encourage hands-on learning in biology, ecology, and environmental science. In some cases, these areas may be located outside school grounds, requiring additional time and organization for student transportation.

· "Green schools":

These represent a more extensive model involving the relocation of classes outside the school environment — often into natural settings — for an extended period of time. The goal is to create a deeper, immersive learning experience that combines education with environmental awareness and physical activity.

In many countries — such as Finland, Sweden, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada — outdoor classrooms are widely used and integrated into national educational programs. These examples demonstrate the growing recognition of the benefits of outdoor learning for cognitive development, creativity, and overall well-being.

Examples of International Outdoor Learning Models

Finnish "Green Schools". Finland is one of the leading countries in the use of natural environments for educational purposes. Permanent outdoor classrooms have been established in forests and open areas, equipped with wooden benches and tables that enable students to learn directly within nature. These outdoor learning environments are often integrated with forest trails and observation points, encouraging active exploration and environmental awareness. The Finnish model highlights the importance of combining formal education with experiential, sensory learning in a natural setting.

Australian Outdoor Learning Programs. Australia has widely adopted the concept of "green schools", where a significant portion of the educational process takes place outdoors — in gardens, parks, and natural reserves. The learning spaces often include mobile structures and tents that serve as adaptable classrooms, allowing teaching to continue under various climatic conditions. The Australian model emphasizes flexibility, sustainability, and the use of outdoor learning to enhance student engagement, creativity, and physical well-being.

European Outdoor Classrooms. In several European countries — including Germany, Sweden, and the United Kingdom — outdoor classrooms have been created using permanent wooden or metal structures that replicate the functionality of traditional indoor classrooms while being situated in gardens or forest environments. These spaces often incorporate educational elements such as native plants, timber, and locally sourced natural materials. The European approach aims to merge architectural design with ecological principles, fostering a direct connection between students and their natural surroundings.

5.3. Research and Findings

Numerous studies demonstrate that students who participate in outdoor learning activities achieve better academic results and exhibit improved physical and emotional well-being. For instance, international research indicates that pupils who regularly attend outdoor classes show higher levels of motivation, stronger engagement, and enhanced social adaptability. These findings suggest that exposure to natural environments contributes not only to cognitive development but also to overall mental health and interpersonal skills. Furthermore, outdoor education promotes concentration, creativity, and environmental awareness, making it an effective complement to traditional classroom learning.

5.4. Challenges and Implementation

Uncertainty and limited resources often present obstacles to the widespread adoption of outdoor classrooms. In addition, climatic conditions and safety considerations must be carefully addressed during the planning phase. Nevertheless, with appropriate design strategies and institutional support, these models can be successfully implemented and can foster positive transformations within the educational system. Properly designing an outdoor classroom involves selecting suitable locations, ensuring safety, and choosing adaptable modular furniture. Improvised natural-material configurations, such as those in Figures 4–5, provide low-cost solutions but often lack writing surfaces.

Figure 4 - Example of improvised outdoor classroom arrangement using natural materials

Note: source – Xiairworld Outdoor Classroom

Figure 5 - Schoolyard-based outdoor learning setup used during educator workshops

Note: source – Stroud Center Workshop Series

When planning an outdoor learning environment, it is essential to analyze the specific site conditions and contextual factors to achieve optimal results. One of the key aspects in this process is determining how the seating modules will be arranged and, more importantly, what type of modules will be used.

Different approaches exist in this regard. One of the most common and economically efficient methods is the use of eco-friendly, naturally available materials instead of manufacturing specialized modules for outdoor classrooms. Although such arrangements are often improvised, they effectively fulfill the intended educational and psychological goals. In many of these cases, however, the lack of a proper desk or writing surface for students remains a practical limitation that needs to be addressed in future designs (Fig. 4–5).

The Second Approach

The second approach requires considerably more resources. It involves the production of specially designed seating modules, often incorporating a surface that allows students to write. The most common implementations include amphitheatrical seating arrangements constructed as permanent, stationary installations. These massive structures provide limited flexibility for reconfiguration and typically do not include individual writing surfaces. Despite their reduced adaptability, such designs offer a durable and visually integrated solution for outdoor learning environments, particularly when intended for larger groups of students (Fig. 1–2).

Modular Design for Extended Outdoor Learning

When longer outdoor learning sessions are required across various subjects, students need suitable conditions for taking notes. This necessitates the development of a module that combines both a seating area and a writing surface. Such a unit must be resistant to weather conditions, lightweight for easy transport, and adaptable for different spatial configurations in accordance with the requirements of the educational process. Possible design variations may include modifications in size, form, or materials, ensuring the module’s suitability for children of different age groups.

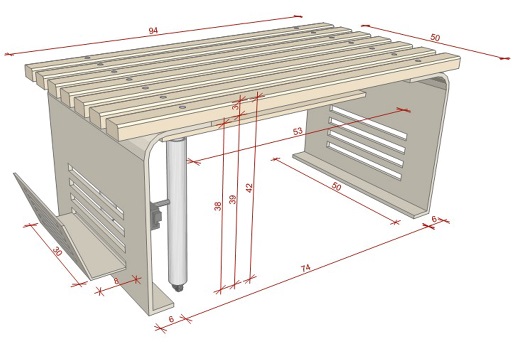

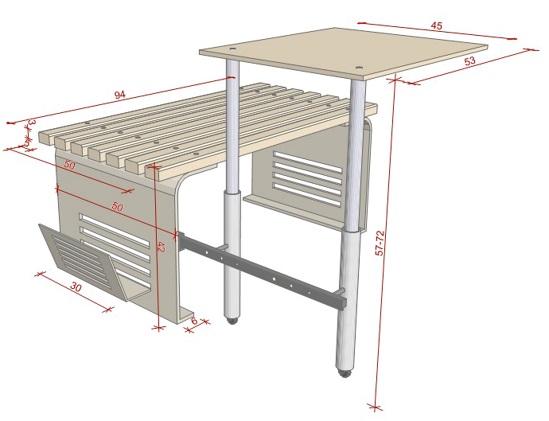

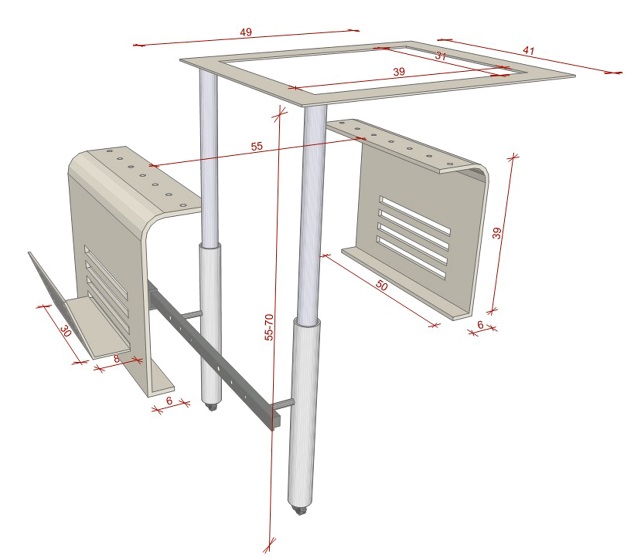

6. A New Concept for a Multifunctional Outdoor Classroom Furniture Module

To enhance the learning experience during outdoor lessons, it is essential to design and produce a multifunctional furniture module that integrates both a seat and a writing surface. The concept emphasizes adaptability for children of various ages and usability under different weather conditions. A key design principle is multifunctionality — the modules should allow for diverse layouts and flexible arrangements depending on the teaching context.

The proposed model includes two main variations:

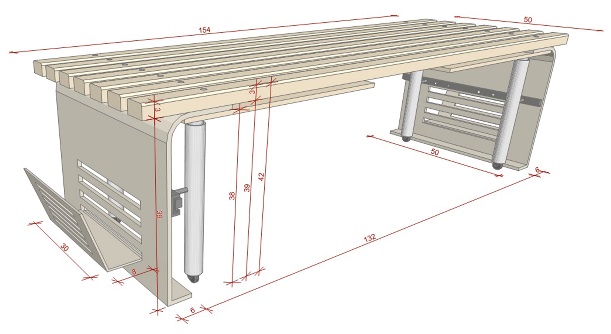

1. Single Module — designed for individual use by one student (Fig. 6–8).

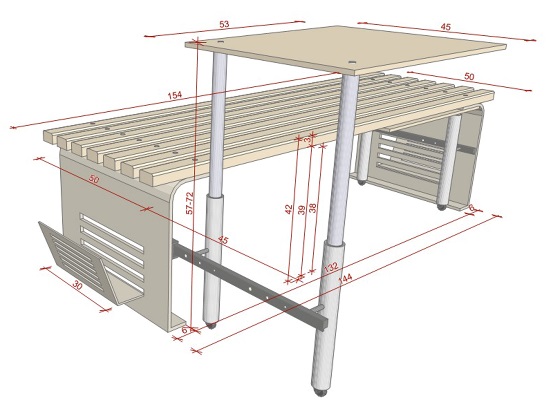

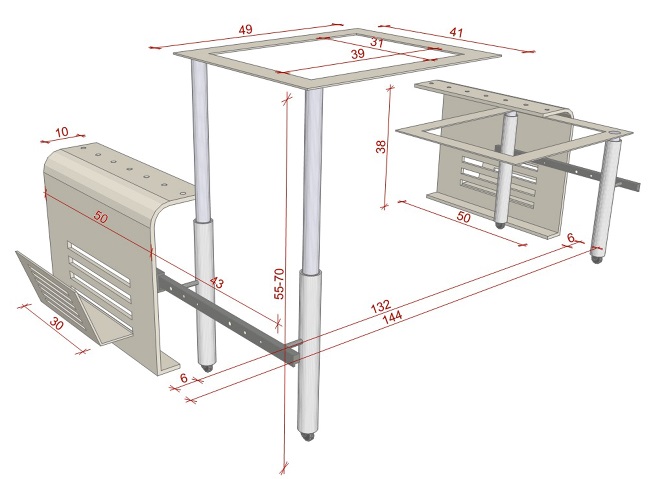

2. Double Module — accommodating two students while maintaining full functionality and ergonomic comfort (Fig. 9–11).

These modules are intended to support outdoor educational environments that encourage active participation, flexibility, and a stronger connection between learning and nature.

Figure 6 - Single seating module with retractable writing surface – axonometric view

Note: author’s design

Figure 7 - Single seating module with pull-out writing desk – axonometric view with dimensions

Note: author’s design

Figure 8 - Structural metal components of the single seating module

Note: author’s design

Figure 9 - Double seating module with retractable writing surface – axonometric view

Note: author’s design

Figure 10 - Double seating module with pull-out writing desk — axonometric view

Note: author’s design

Figure 11 - Structural metal components of the double seating module

Note: author’s design

Variant 1 — Module with Metal Frame and Wooden Elements

The module is designed with a metal load-bearing structure, ensuring both strength and durability. The seat is composed of solid wood elements, while the working surface is made of laminated timber, providing resistance to mechanical stress. All wooden components are treated with impregnating agents and protective varnishes that safeguard the material from environmental factors such as moisture, ultraviolet radiation, and temperature fluctuations.

The worktop is height-adjustable, supported by telescopic tubular elements allowing several levels of elevation. This feature enables adaptation to different age groups and various learning activities. For enhanced functionality, the module incorporates a sliding mechanism that allows the worktop to retract beneath the seat, thereby increasing its compactness and mobility.

A side support element includes a dedicated space for the storage of textbooks and learning materials. The sliding mechanism of the worktop operates on the principle of drawer runners, ensuring ease of use and straightforward construction without the need for complex engineering solutions.

The legs of the structure are equipped with wheels and locking stoppers, allowing for easy relocation and stable positioning when in use.

While the use of wooden components strengthens the connection with nature and enhances the aesthetic appeal of the module, it reduces its long-term resistance to outdoor weather conditions and therefore requires periodic maintenance.

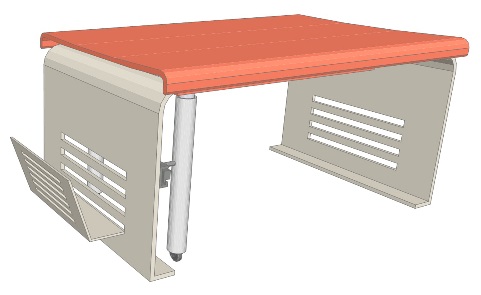

Figure 12 - Double seating module in lightweight weather-resistant version (plastic seat and tabletop)

Note: author’s design

Figure 13 - Single seating module in lightweight weather-resistant version (plastic seat and tabletop)

Note: author’s design

Variant 2 — Lightweight Module with Weather-Resistant Materials

The second version presents a significantly lighter design, utilizing materials with enhanced resistance to atmospheric conditions. The use of plastic elements increases the product’s durability while reducing its overall weight — an important advantage given that the module is intended to be mobile and used by children (Fig. 12–13).

In terms of structural components and mechanisms, the design remains consistent with the previous variant, ensuring stability, functionality, and ease of use.

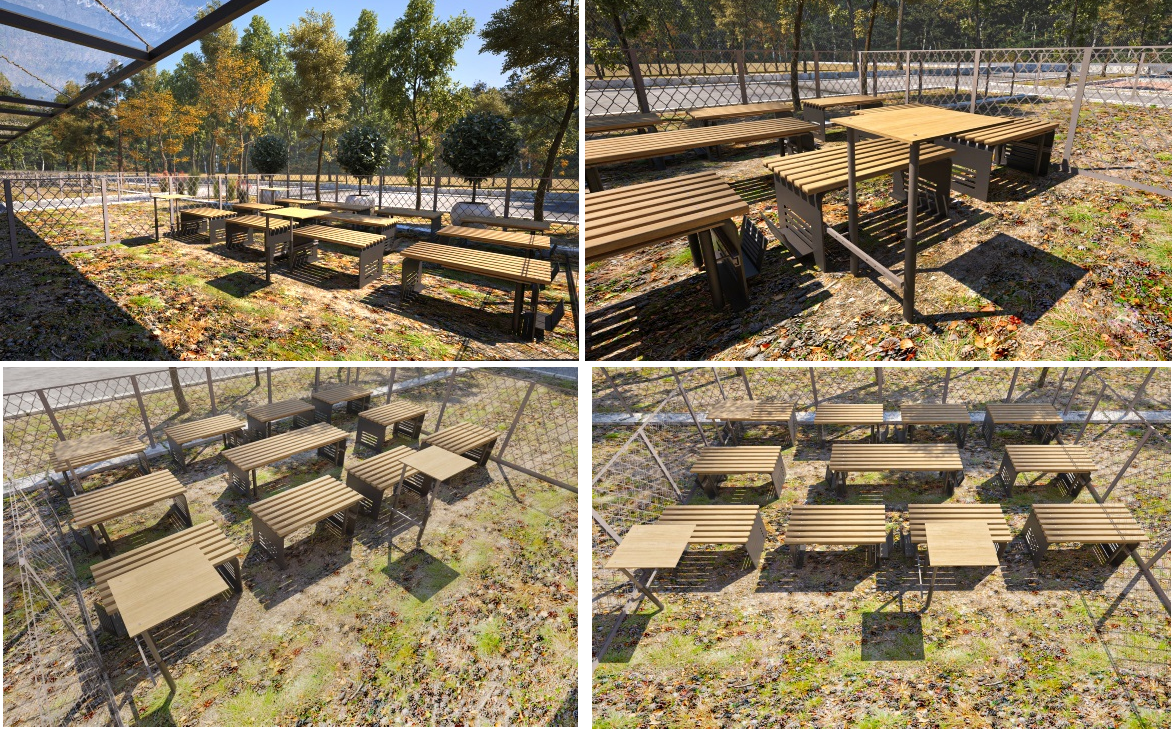

Examples of Placement of the Proposed Module in Outdoor Classrooms (Fig. 14–15).

As part of the author’s project for a "Primary Private School in Sofia", several options for positioning the designed module have been proposed. The concept suggests placing the modules in the courtyard areas adjacent to the ground-floor classrooms designated for early education. Two layout options are presented.

The accompanying 3D visualizations illustrate both the single and double module versions, featuring a retractable and extendable writing surface (Fig. 14–15).

Figure 14 - Orthogonal layout arrangement of single and double modules in the outdoor classroom

Note: author’s project for "Primary Private School", Sofia

Figure 15 - Semicircular placement of modules in outdoor learning configuration

Note: author’s project for "Primary Private School", Sofia

7. Conclusion

The impact of global urbanization and digitalization on children is substantial and multifaceted, posing serious challenges related to the mental and physical health of young people. The identified issues, such as nature deficit disorder and its associated health problems, underscore the need to reconsider school environments and educational practices. Integrating nature into the educational process can not only enhance students’ well-being but also promote their social engagement and physical activity.

The proposed solutions, including the transformation of school spaces and the concept of outdoor classrooms, offer innovative approaches to addressing these challenges. By adapting existing school infrastructure and creating multifunctional spaces that encourage interaction with nature, we can improve the conditions for children’s learning and development.

In conclusion, it is essential to continue researching the effects of urbanization and digitalization on the younger generation and to promote the active involvement of educational institutions, parents, and society in efforts to restore the connection between children and nature. Only through collective action can we ensure a healthy and supportive environment for future generations.